Kim Mordaunt 2013 Laos/Thailand/Australia

Starring: Sitthiphon Disamoe, Loungnam Kaosainam, Suthep Po-ngam, Bunsri Yindi, Alice Keohavong, Sumrit Warin

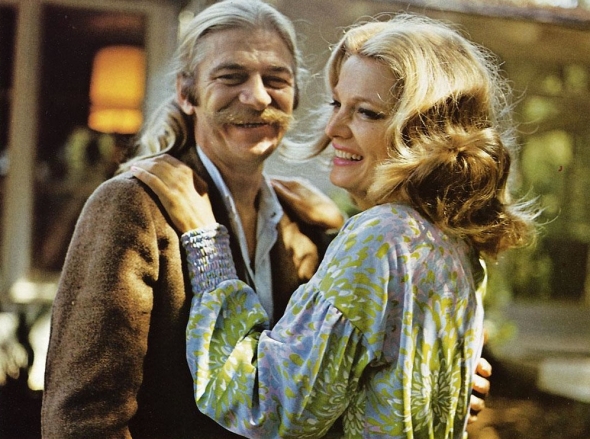

Kim Mordaunt's story of childhood, poverty and hope in modern Laos, The Rocket, has been compared in many reviews to 2012's Beasts Of The Southern Wild but, while both feature children navigating flood-hit nature, that's about as far as the comparisons go and such attempts at association are pretty uncomplimentary to this film. The key here is magical realism and a focus on tradition with 10 year old Ahlo labelled as a cursed being by his foul-mouthed, doomsayer grandmother because of his status as a surviving twin (his sibling was stillborn) and forcibly relocated from his village to a government-sponsored shanty town by officials who want to flood the region and build a new dam. While there he meets orphaned child Kia and her hilarious, permanently soused, deathly Uncle Purple, so called because of his obsession with James Brown and his propensity to dress up (and dance) like him. But, much like many of the other characters, there's a darkness to this apparent clown as it turns out his beloved suit was given to him by the American Embassy, possibly as a gift for collaborating with them. Later Ahlo sees a photo showing Purple as a child soldier and seeks his expert tuition to help make a rocket for the central competition and we understand that his patent mixture of senility and whiskey may actually be the coping mechanism of a traumatised old man. Thankfully this isn't dwelled on too heavily and the meat of the film concentrates on the sweet friendship between the two children and their attempts to better their lot. Both are really outstanding in the roles punctuating the film with energy, heart, a complete lack of fear and, in Kia's case, a sense of eternal optimism that only threatens to disappear when Ahlo does. The direction falters on occasion and threatens to dip into sentimentality but things are kept strong by the charm of the leads, the dramatic and funny fable-like story and a picturesque setting that should delight arthouse and mainstream audiences alike.